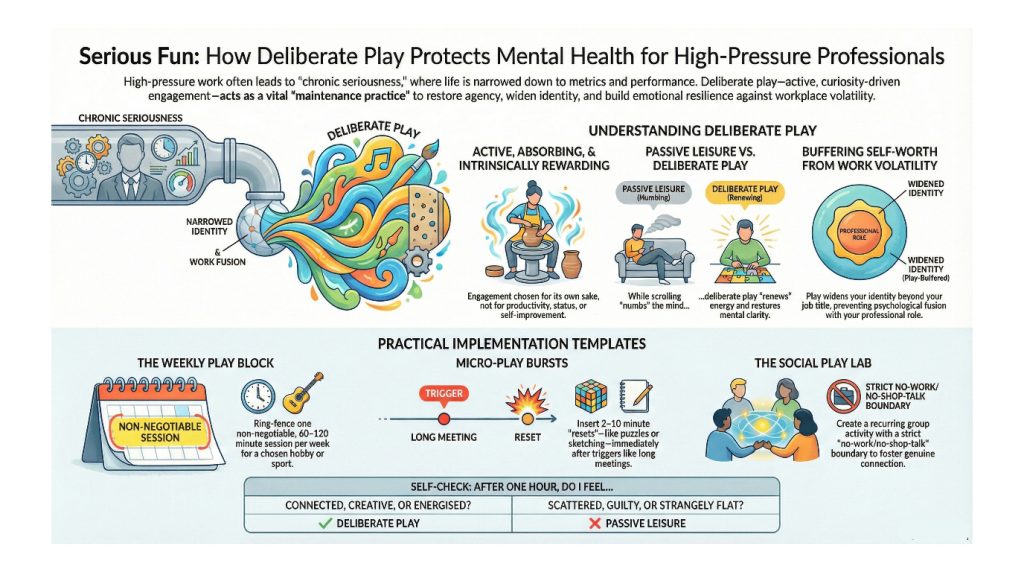

Serious fun matters more than ever when your days are packed with responsibility and decision‑making. This article gives you a clear definition of deliberate play, shows how it differs from passive downtime, and offers concrete templates you can start this week.

## What is “deliberate play”?

Deliberate play is **active, absorbing, and intrinsically rewarding** activity you choose for its own sake, not for productivity, status, or self‑improvement.

It has three key features:

– You are actively engaged (mentally, physically, or both), not just consuming.

– There is some element of exploration, challenge, or creativity.

– The primary goal is enjoyment and curiosity, not achievement or optimization.

For high‑pressure professionals, deliberate play is the opposite of “squeezing in one more productive thing.” It is a protected space where it is safe to be non‑efficient, experimental, and occasionally bad at something.

## Play vs passive leisure

Not all rest is created equal. A lot of what passes as “relaxing” for busy professionals is actually low‑quality recovery.

– **Passive leisure**: scrolling, binge‑watching, background TV, aimless web surfing, comfort snacking, or drinking to unwind. These are easy to start and require no planning, but they rarely restore mental clarity or emotional resilience. You finish feeling dulled rather than refreshed.

– **Deliberate play**: board games with friends, learning an instrument, pickup sport, creative writing, dancing, improv, tinkering with Lego or model kits, playing with your kids in a way that engages you, not just supervising.

Both have a place, but they are not interchangeable. Passive leisure numbs. Deliberate play renews.

A useful self‑check:

– After an hour of this activity, do I feel more connected, creative, or energised? If yes, it is likely play.

– Do I feel more scattered, guilty, or strangely flat? That is a warning sign that my “rest” has drifted into passive escape.

## How deliberate play protects mental health

High‑pressure work tends to narrow life into a few channels: email, meetings, metrics, and family logistics. Over time this creates a psychological pattern of **chronic seriousness**: everything feels like a project, a risk, or a performance.

Deliberate play counteracts that in several ways:

– It widens your identity beyond your role. When you are a guitarist, swimmer, chess player, or improviser for a few hours a week, you are no longer psychologically fused with being a manager, founder, or professional. This buffers self‑worth from work volatility.

– It restores a sense of agency. Play is chosen, not assigned. In many careers, most of your calendar is reactive. Play reintroduces spaces where you decide the rules, pace, and level of challenge.

– It interrupts ruminative loops. Absorbing play (flow) recruits attention so fully that worry and self‑criticism temporarily lose their grip. This is not avoidance; it is a healthy “reset” that often allows you to return with a clearer perspective.

– It introduces safe novelty and experimentation. Many mental health issues are amplified by rigid routines and avoidance of uncertainty. Play lets you practice being with mild risk and surprise in a low‑stakes context.

For midlife professionals facing cognitive load, role strain, and background anxiety, deliberate play is not indulgence; it is a maintenance practice for mood, resilience, and long‑term performance.